How to use the dictionary

From our present-day point of view – perhaps even from the contemporary viewpoint – it is not easy to use Schmeller’s dictionary. It has a few peculiarities.

Not in strict alphabetical order

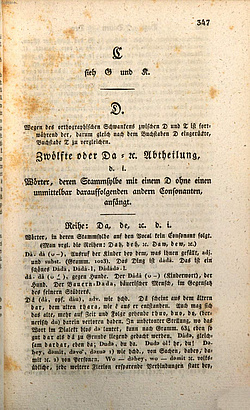

Dialect regions in Bavaria are quite diverse, and the pronunciation of a word can vary from village to village. For this reason, Schmeller deemed it necessary to use a non-alphabetical order for the dictionary. Instead of strict alphabetical sequence, the words are ordered primarily by their consonants (the so-called “stem syllable principle”). He himself calls this the “AUBC“-order.

The sequence of words in the dictionary might at first glance seem complicated, but once the user is used to it, it can simplify the search for particular dialect words. That this alphabetical order does indeed make sense is shown by subsequent dialect dictionaries such as the Dictionary of Swiss German Dialects, which chose to use Schmeller’s alphabetical order. Finding the right word entry does cause some difficulty for the unpractised user, but there is a strict alphabetical index appended to the second volume of the second edition.

Contemporary and elder vocabulary in one dictionary

The dictionary contains not only the vocabulary of the contemporary dialects, but also records words which were no longer in general usage even in Schmeller’s day. Schmeller writes:

This dictionary is … not merely an Idioticon containing expressions occurring in the living dialects, and not only a glossarium of those expressions found in old texts and documents; it is both at the same time. That which is now, finds its most natural explanation in that which once was, and vice versa” (Einleitung VII).

Thus Schmeller aims to record not only the specialities of the dialect, but the entire vocabulary. Nowadays, such dictionaries are state of the art, but in Schmeller’s time the idea was new. Just as the representation of the various and varied dialect regions permits the comparison of the living dialects in their geographical complexity, so the historical dimension allows the comparison of historical stages of the language in their temporal sequence. Schmeller’s sources go back to the earliest vernacular texts. But the main sources are the spoken dialects of his age, of which the many proverbs, mocking songs and other verses from the vernacular which he collected and quotes as examples of everyday language are an impressive testimony.

Differences to standard German usage

Schmeller emphasizes those meanings of a word which differ from Standard German usage. If the meaning in the dialects corresponds to Standard German, he simply writes: “Wie hochdt.” (as High German). This means that the meaning in question can be looked up in Johann Christoph Adelung’s dictionary “Grammatisch-kritischen Wörterbuch der hochdeutschen Mundart” (²Leipzig 1793-1801). Schmeller intended that his own dictionary should – among other things – complement dictionaries of the German standard language, in particular Adelung’s, contributing the usages particular to the dialect.

Schmeller’s dictionary articles again and again contain interesting digressions and detailed ethnographic descriptions. Many of these are derived from Schmeller’s own hand-written supplementary notes in his private copy of the first edition of the dictionary, adopted unchanged by Fromman in the second edition. His descriptions of Bavarian folk customs are frequently quoted, so from the dictionary articles Kammerfenster (chamber window) and Kammer (bed-chamber):

„auf dem Lande vorzüglich das Fenster an der Kammer, worin ein unverheirathetes, mannbares Mädchen schläft, sie sey nun die Dirne oder die Tochter vom Hause. An diesem Fenster seufzen die noch unerhörten ländlichen Liebhaber, freuen sich Ihres Glückes die erhörten, jammern und verzweifeln oder trotzen und schelten die verschmähten“.

“in the countryside especially the window of the bed-chamber, wherein an unwed, nubile girl sleeps, be she the maid or the daughter of the farm. At this window, the unrequited rural admirers sigh, the requited rejoice at their good fortune, the scorned lament and despair or sulk and swear”.

An’s, unter’s Kammerfenster gen zu Einer, to pay a girl a night-time visit at the window of – and even in – her bed-chamber.

An’s, unter’s Kammerfenster gen zu Einer, einem Mädchen des Nachts am Fenster ihrer Schlafkammer, und wol in dieser, einen Besuch machen.“

Or on the word Milch (milk) (I, 1591):

„Am Jacobitag begeben sich die Eigenthümer von Alpen-Vieh aus ihren Dörfern auf die Alpen, um nachzusehen, welchen Alpen-Nutzen, d.h. Ertrag an Milch, Butter etc. sie sich von jedem Stück, das den Sommer auf der Alpe zubringt, versprechen dürfen. Es wird zu diesem Behufe die Milch gemessen, welche jede Kuh an diesem Abend und den folgenden Morgen gibt. Nach dieser wird der Anschlag auf die ganze Sömmerungszeit gemacht. Daß dieses Milchmessen, vom Tag auch Jakobsen genannt, bey dem heitern Muth der Oberländer zu einer Art von Fest geworden seyn müsse, ist begreiflich. Nicht blos der Hausvater, sondern auch die männlichen und weiblichen Hausgenossen besuchen bey der Gelegenheit ihre Gespielinnen, die sich als Sendinnen auf der grünen Höhe befinden“.

On Saint James’s Day, the owners of the animals sent to mountain pasture ascend to the pastures in order to ascertain what Alpen-Nutzen they can reckon with from each animal on the mountain, i.e. how much milk, butter etc. To this end, the amount of milk is measured which each cow gives on this evening and on the following morning. This forms the basis for calculating the amount for the entire period at pasture on the mountain. It is understandable, given the cheerful nature of the Upper Bavarians, that this Milchmessen (measuring of the milk), also called Jacobsen, after the Saint’s day, must develop into a sort of festival. Not only the farmer himself, but all the male and female members of the household, come along to visit their playmates who are serving as dairymaids and herdswomen on the Alpine meadows.

Literature quoted

Bremer, Ernst und Walter Hoffmann: Wissenschaftsorganisation und Forschungseinrichtungen der Dialektologie, in: Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung, hg. von W. Besch u.a., Berlin/New York 1982, Bd I, S. 202–231.

Reiffenstein, Ingo: Zur Geschichte, Anlage und Bedeutung des Bayerischen Wörterbuches, in: Zeitschrift für Bayerische Landesgeschichte 48 (1985), 17–39.

Schmeller, Johann Andreas: Sprache der Baiern. In: Oberbayerisches Archiv 43 (1886), 69–81.

Schmeller, Johann Andreas: Die Mundarten Bayerns grammatisch dargestellt. München 1821.

Schmeller, Johann Andreas: Bayerisches Wörterbuch. Teile 1-4, Stuttgart und Tübingen 1827–1837.

Schmeller, Johann Andreas: Bayerisches Wörterbuch. 2., von G. Karl Frommann bearb. Auflage. Bde 1-2, München 1872–1877.